Over the next three weeks, we’re taking a focused look at one of the eight points: One-Pointed Attention. We’ll have an opportunity to explore this topic through a variety of materials: an online workshop (today!), an experiment to try at home, and a reading and video study.

Below is a reading from Easwaran’s chapter on One-Pointed Attention from Passage Meditation. Part of this excerpt was used in today’s Online Workshop, and if you weren’t able to attend, you can jump right into the discussion now. For those of you who took part in the Workshop, this is a chance to share your insights with others, and take them further for yourself.

Let’s start this month’s theme by trying out an experiment. Identify a routine time in daily life when you would like to be more one-pointed, and think about the benefits being more one-pointed might bring.

Next, plan what you’ll need to do to remind yourself about being more one-pointed during that time. Here’s an example: “I’d like to be more one-pointed as I eat my breakfast in the morning before work. I think it will help me be calmer and more focused at work especially when facing a stressful project. I’m going to remember my intentions by putting a copy of Passage Meditation on my dining room table right by where I sit.”

We’d love to hear your ideas! Please share in the comments below to inspire others and boost your enthusiasm. Consider working on this experiment during the coming week.

Watch this short video for tips on how to use the comments feature.

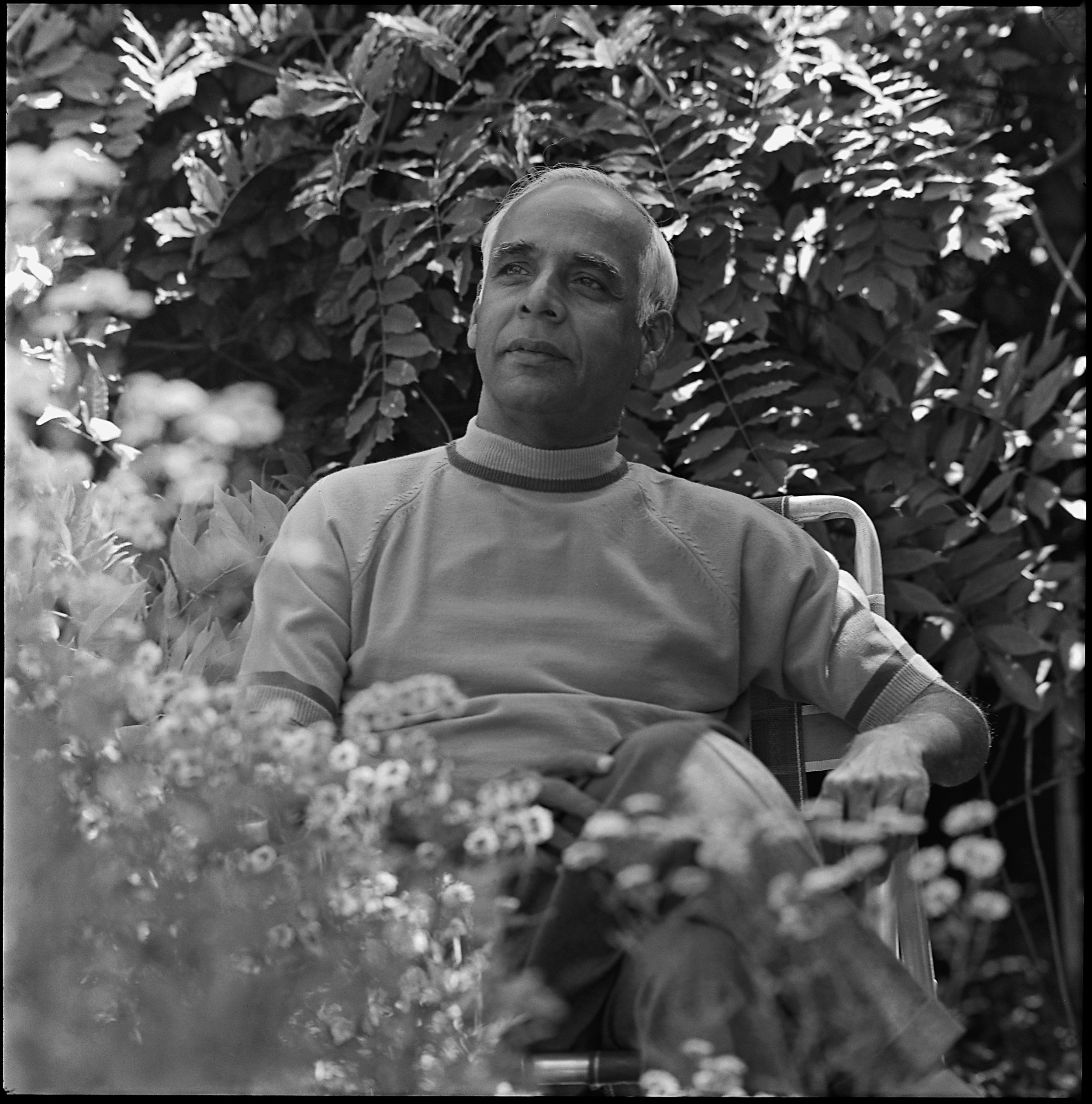

The excerpt below is from Passage Meditation, by Eknath Easwaran.

The Benefits of One-Pointedness

The one-pointed mind, once we have obtained it, gives us tremendous loyalty and steadfastness. Like grasshoppers jumping from one blade of grass to another, people who cannot concentrate move from thing to thing, activity to activity, person to person. On the other hand, those who can concentrate know how to remain still and absorbed. Such people are capable of sustained endeavor.

I’m reminded of a story about a great Indian musician, Ustad Allauddin Khan. When Ravi Shankar, the sitarist, was a young man, he approached Khan Sahib for lessons, passionately promising to be a diligent pupil. The master turned his practiced eye upon Ravi and detected in his clothes and manner the signs of a dilettante. He said, “I don’t teach butterflies.” Fortunately, Ravi Shankar was able after many months – a test of his determination – to persuade the master to reconsider. But we can readily understand the teacher’s reluctance to waste his precious gift on someone who might jump from interest to interest, dissipating all his creative energies.

People who cannot meet a challenge or turn in a good performance often suffer from a diffuse mind and not from any inherent incapacity. They may say, “I don’t like this job,” or “This isn’t my kind of work,” but actually they may just not now how to gather and use their powers. If they did, they might find that they do like the job, and that they can perform it competently. Whenever a task has seemed distasteful to me – and we all have to do such things at times – I have found that if I can give more attention to the work, it becomes more satisfying. We tend to think that unpleasantness is a quality of the job itself; more often it is a condition in the mind of the doer.

The same may be said for boredom. Few jobs are boring; we are bored chiefly because our minds are divided. Part of the mind performs the work at hand and part tries not to; part earns his wages while the other part sneaks out to do something else or tries to persuade the working half to quit. They fight over these contrary purposes, and this warfare consumes a tremendous amount of vital energy. We begin to feel fatigued, inattentive, restless, or bored; a grayness, a sort of pallor, covers everything. How time conscious we become! The hours creep, and the job, if it gets done at all, suffers. The result is a very ordinary, minimal performance, since hardly any energy remains with which to work; most of it goes to repair the sabotage by the unwilling worker.

When the mind is unified and fully employed at a task, we have abundant energy. The work, particularly if routine, is dispatched efficiently and easily, and we see it in the context of the whole into which it fits. We feel engaged; time does not press on us. Interestingly too, it seems to be a spiritual law that if we can concentrate fully on what we are doing, opportunities worthy of our concentration come along. This has been demonstrated over and over in the lives not only of mystics but of artists, scientists, and statesmen as well.